Awright. I think we've hit the high point of the whole zombie apocalypse thing. Time to pack it up and move on, because it ain't gonna get much better than this and everything else is either a poor imitation or just wasting our time.

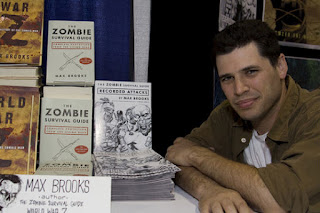

This article has been stewing in the cooker for a long time, but I never had the guts to write it. Aside from the fact that I really like this book and its predecessor The Zombie Survival Guide, I feel that this takes the Romero zombie as far as it can possibly go. So, talking about this means talking about the whole zombie sub-genre and that's a loooooong conversation.

Deep breath. This is a day for decisive action.

Here we go.

Okay, so everyone calls The Zombie Survival Guide a comedy, but aside from the absurdity inherent in the idea of an Army-style survival guide for a completely absurd apocalypse the material is played straight. I don't know much about wilderness survival or military maneuvers, but the advice seems legit enough. It also appeals directly to the darkly pleasant side of the zombie fantasy: you've survived in a war-torn wasteland. You're hardy and self-sufficient, cool in a crisis and skilled at war. Post apocalyptic stories are one or two steps away from westerns, and to understand the western is to understand America.

It makes sense that the zombie came back into popularity around the same time as new millennium panic kicked off. There's something about our cultural mentality that has a dark fascination with apocalypses. Personally, I think it has something to do with our parents growing up during the A-bomb crisis and the Vietnam war, my generation growing up with 9/11, and the overall crazy Four Horsemen fundie Bible Belt bullshit that sits at the center of our nation.

Plus, at their heart, the zombies are us. They are everywhere we are, they wear our costumes, they suffer our death, and the relentlessly approach us with soulless eyes. And if they catch you, they'll eat you alive.

So zombies do what a good horror critter is supposed to do. It gets under your skin. The rules are simple, the images are grostesque, and death at their hands is ghastly. But there's only so much you can do with them.

The vast majority of zombie stories are siege stories. People are under assault, people barricade themselves in, the stress gets to the survivors, and shit eventually goes wrong. It's a fine story but it's very overdone. There's also an aspect of zombie tales that appeal to a very American Libertarianism sense of self-reliance and individualism. I got my gun, I got my dog, and I can carve a place for myself out of this hostile land.

Some people take that shit really, really seriously. Meet someone who claims to be a zombie nut and ninety nine percent of the time you're meeting with someone who secretly wants a zombie uprising. I have a sneaking suspicion that the vast majority of actual survivors would be in military bases or living in isolated communities. I'm a creature of cities. My ass would be grass.

Anyway, there are only so many stories that you can tell with zombies. People keep trying, and when they don't actually want to do zombies, they do spider critters or creatures made of snow. If the apocalypse has already been tackled on an intimate level, the only way to go is to go bigger. Make it about humanity. How do different people, different cultures, different value systems deal with the rise of the dead?

In a lot of ways, World War Z is pretty much the final word on zombie apocalypses. Rather than focusing on one group of knuckleheads, Brooks tells the story from dozens of different angles. How would celebrities deal with this? How would soldiers? How would pharmaceutical companies try to cash in? What would a major evacuation at the mouth of the Ganges be like? All of these stories could probably make individual novels, but Brooks threads them all together into a Ken Burns-style documentary of the event as survivors tell the story of society trying to rebuild itself.

It's brilliant. It's one of the best horror novels of the last ten years.

The thing that rugged apocalypse stories don't really get is that if the zombies arise, the individual is ultimately meaningless. Some random tough guy asshole may make it through the narrative, but then what? He continues on until he falls off a cliff or his luck fails and he's monster food.

Therefore, the zombie apocalypse tale must be about humanity itself. This is the thing that pulls us together. We got our iphones and our youporn and our netflix and our Republican primaries and all the other crap we use to feather our nests. The cost in human life to scorch the earth would be catastrophic, but what if we rose up afterward and worked together in rebuilding what is hopefully a better world?

Idealistic? Sure. Stupid? Absolutely. But the secret appeal of the post-apocalypse story is that the world is scrubbed clean. To quote the great poet Billy Idol: "and there's nothin' pure in this world. Look for something left in this world...."

"Start again."

Brooks does something I want to do. He takes tropes that are getting pretty ragged and tells a story that isn't about monsters and mayhem, but our shared humanity. It ain't perfect. Too many of his voices sound interchangeable and, while the chapters centered around the hikkikomori in Japan touched my inner weeaboo, the blind woodsman with the sword lopping off heads was a little ridiculous. He mentioned a secret society of zombie hunters in his Survive A Zombie Apocalypse book, but it's something that belongs in a comic book. Still,

Quibbles. This really is one of the best horror books of the last ten years. It's also the final word on the zombie thing. There isn't much left to do with Romero zombies. Hell, Romero can't even do anything with them any more. Brooks nailed it. Time to find something new.

Oh, Brooks wrote a good comic featuring tales of the zombie war. Also, Brad Pitt is doing a movie version of this. Oy.